Portable Infinities explores how intimate forms contain expansive possibilities, treating material and gesture as portable architectures that carry memories, associations, and experiences. Through drawing, assemblage, textile thinking, and incremental construction, these practices reveal how openness emerges from restraint and how the infinite can be suggested through structural clarity, simple geometries, and the quiet accumulation of acts.

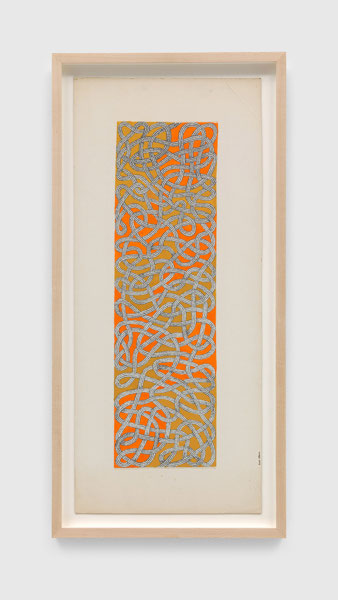

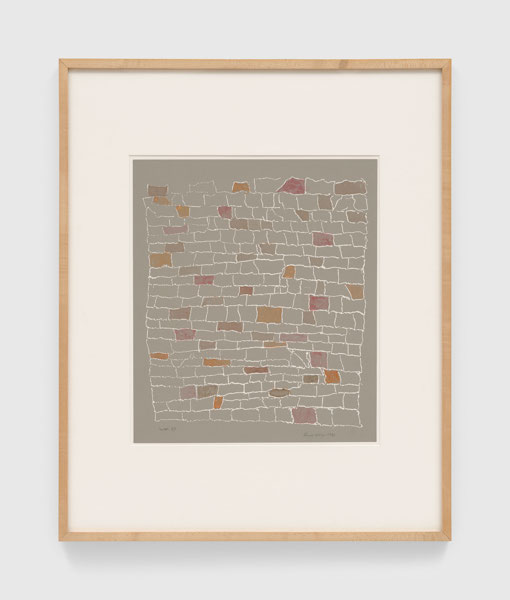

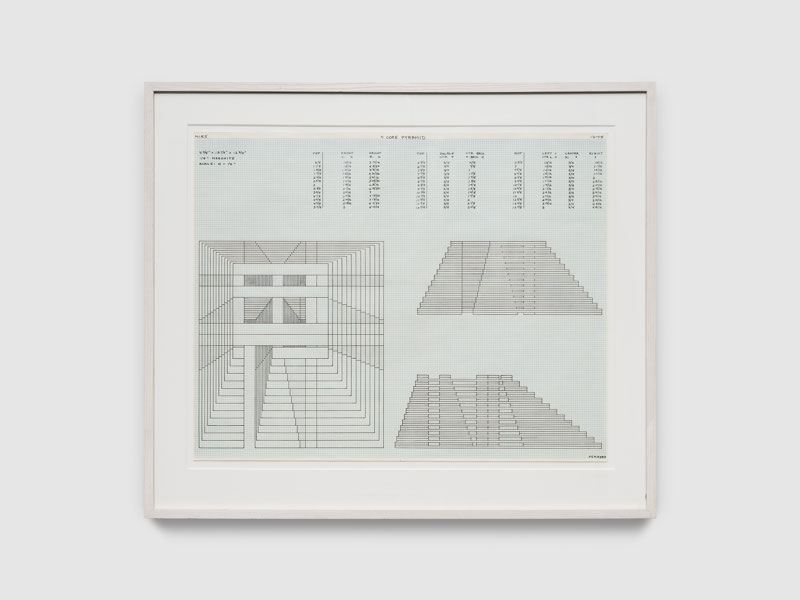

Anni Albers’s works on paper translate the logic of weaving into visual structures that move between gridded clarity and fluid, interlaced lines. Wall IV, with its irregular brick-like forms, distills architectural patterning into a modular composition animated by subtle shifts in spacing and scale. In Drawing for a Rug, blue and white lines curve and intertwine across an ochre and orange ground, forming pathways that suggest movement, entanglement, and the layered decisions of hand and eye. Jackie Ferrara’s Wallyard 11 establishes an architectural presence that feels both grounded and generative. The sculpture’s stacked progression suggests a column developing through accumulated decisions, mirroring the way Albers’s modules gather into coherent systems. Both artists approach structure as a living pattern shaped by repetition, material responsiveness, and close attention to proportion.

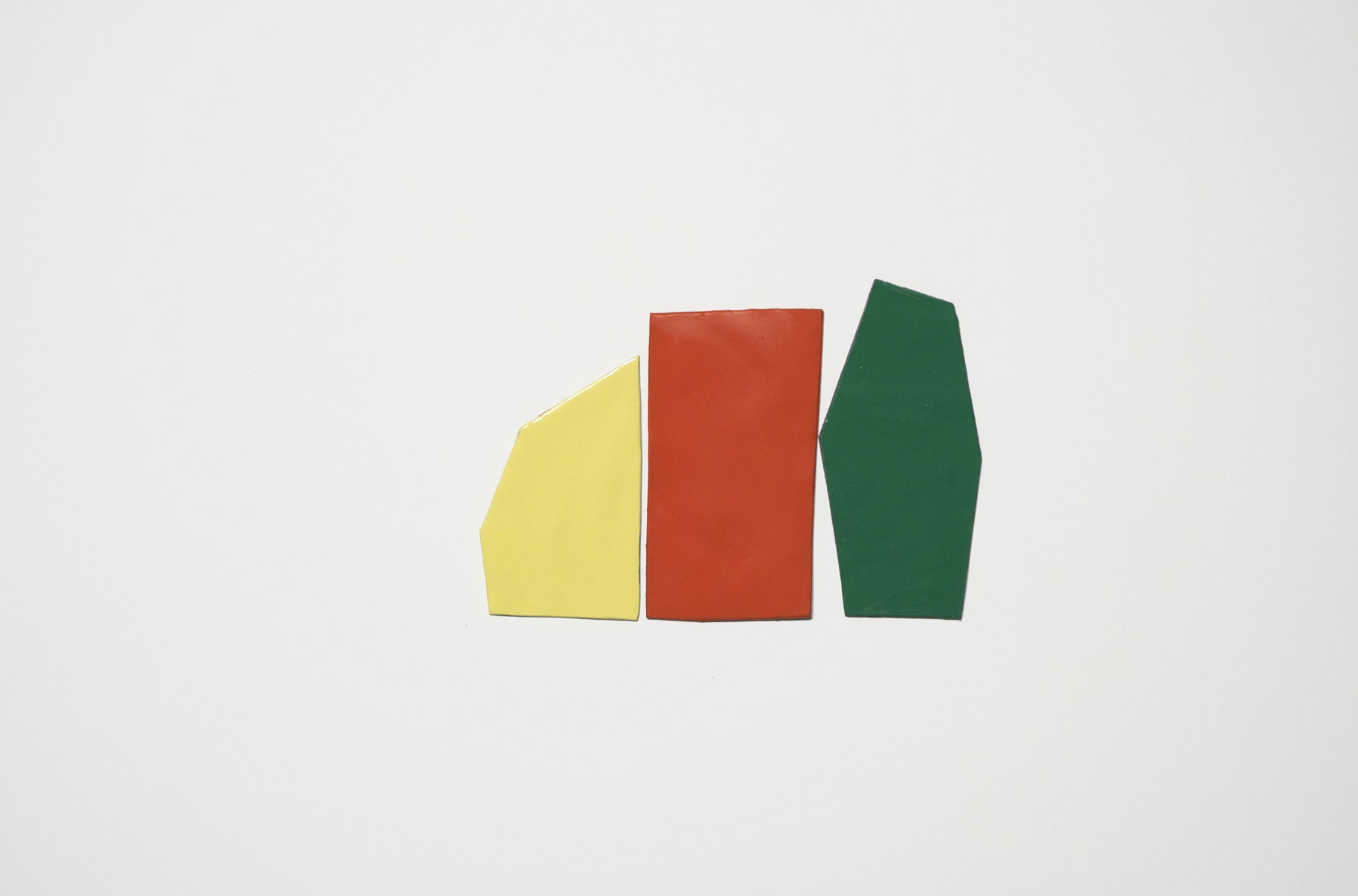

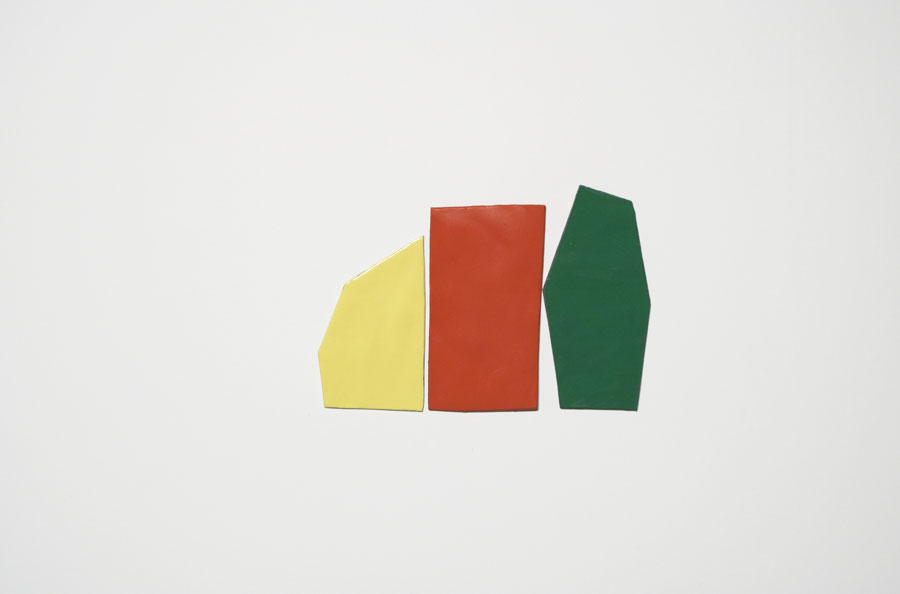

Nancy Brooks Brody extends these concerns into corporeal and perceptual space. Their Merce Drawings begin with low-resolution photographs of Cunningham dancers printed onto newsprint, where a head tilt or shift of weight becomes a fixed point guiding the drawn line. Each iteration underscores the live act of drawing and the inscription of movement onto time. In the Color Forms series, enamel-painted lead shapes embedded into shallow clefts in the wall create intervals that shift with light and proximity. Brody’s practice shares with Albers and Ferrara a commitment to calibrated structure, yet introduces the body as both source and residue, allowing movement and unpredictability to enter the field.

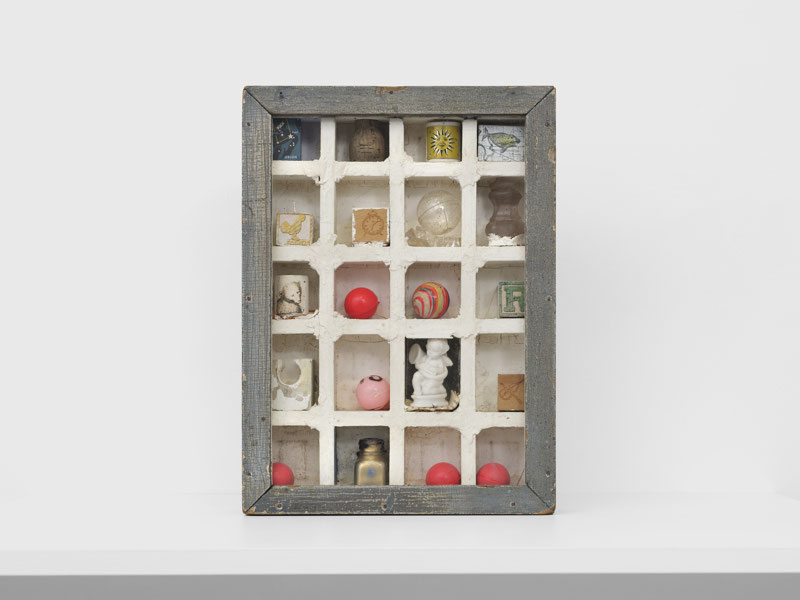

Joseph Cornell’s Dovecote box transforms modest materials into an intimate architecture where structure and imagination meet. Its grid of small, white, crusted compartments holds toys, blocks, a glass jar, a figurine, and rubber balls, balancing formal order with associative possibility. A second, mostly monochromatic assemblage containing a pipe, tiny glasses, a ball, string, and collage introduces a more celestial register, where objects seem to hover within a restrained interior like fragments of a quiet constellation. Cornell’s works function as portable observatories in which objects, textures, and memories form shifting relationships.

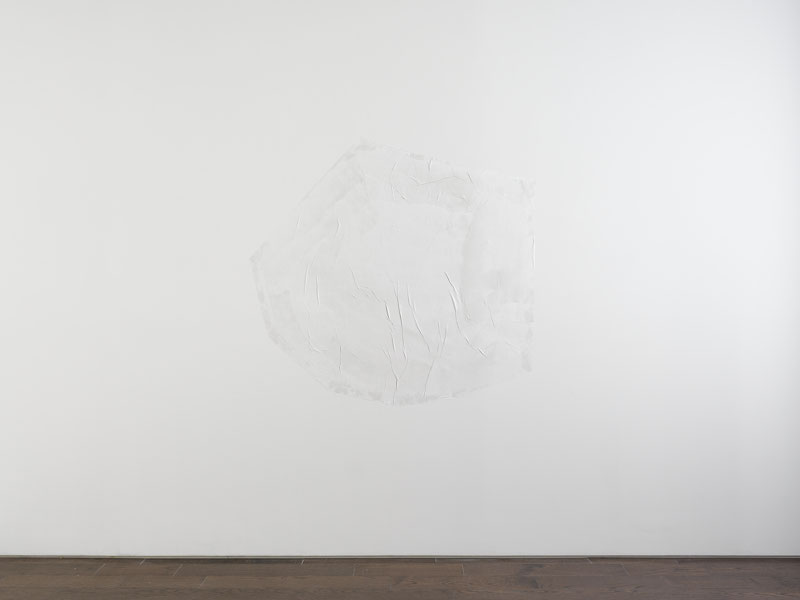

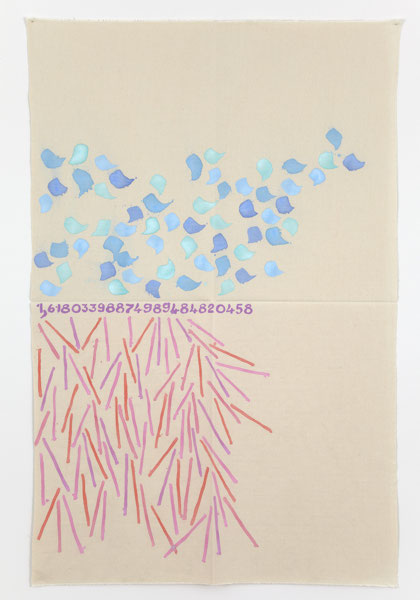

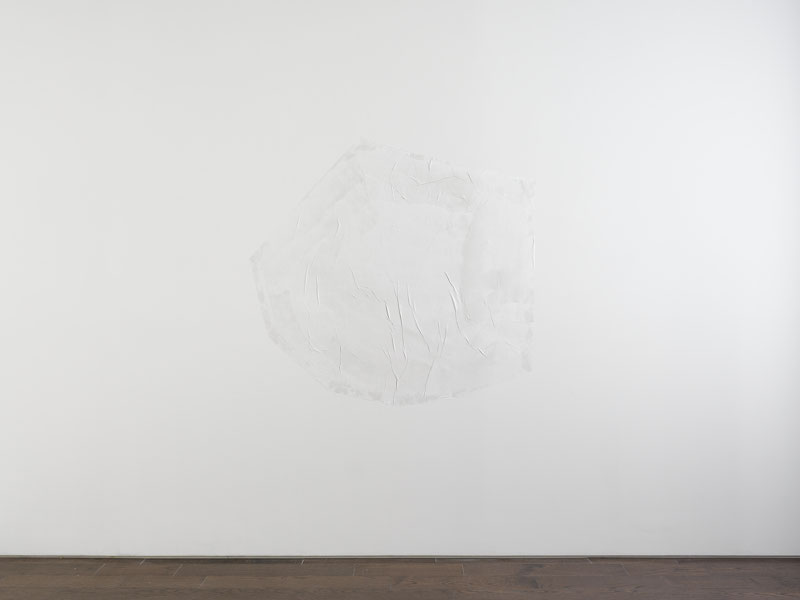

Giorgio Griffa and Richard Tuttle share an interest in surface, support, and the generative potential of slight, provisional gestures. Griffa’s Canone aureo 458 treats the Golden Ratio as a living structure that extends indefinitely while unfolding across a finite canvas. Painted on unstretched canvas, the drifting numerals record a gesture that is both provisional and continuous, grounding conceptual vastness within intimacy. Tuttle’s Paper Octagonal also emerges from the behavior of materials rather than predetermined geometry. Subtle creases and irregularities caused by adhesive reveal how paper responds to gravity and wall surface. By naming the shape an Octagonal, Tuttle shifts attention from ideal form to particular instance, allowing the work to register its own making. Together, Griffa and Tuttle privilege the autonomy of the support and the quiet intelligence of material, demonstrating how the infinite can reside in slight deviations of color, contour, and touch.

Sean Horton & Parker Jones, December 2025