Drawing matter brings together artists whose work draws upon the conventions and techniques of drawing in ways that extend beyond traditional practices, using a variety of meaningful materialities. By broadening the scope of the medium, they offer a form of plastic drawing, akin to certain photographs from the latter half of the 20th century.

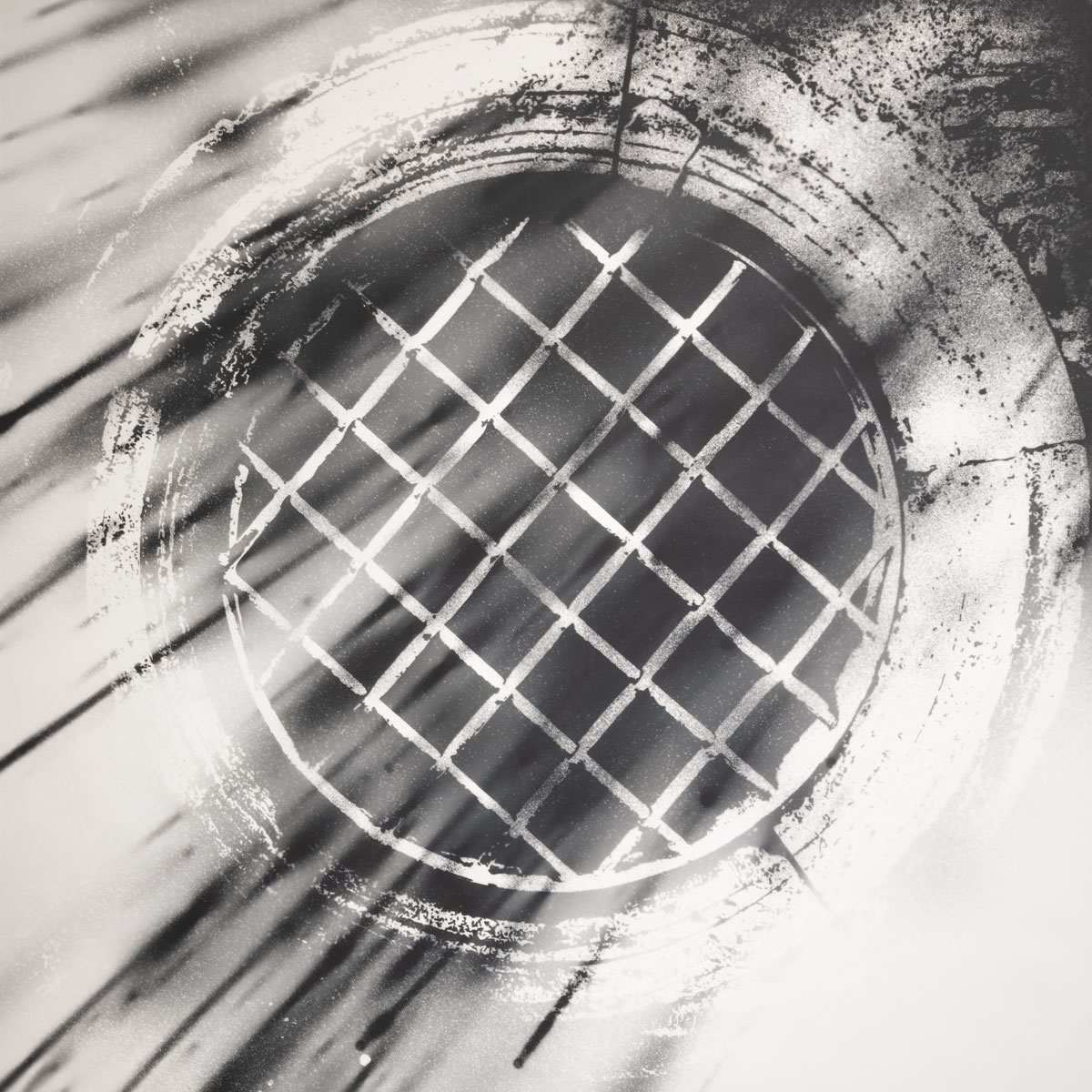

Betting on drawing’s ability to exist beyond the material assumptions we tend to assign to it, Lionel Sabatté achieves a virtuoso, minimalist style through radical restraint. The artist’s graphic gesture–whose practice constantly redefines our relationship with reality and discarded materials–begins with a broom, which he uses to collect dust from the Châtelet metro station in Paris. As he hunts for this material with high graphic potential, he is simultaneously pushing drawing to its very limits; those of a renewal that strangely harkens back its origins. Lionel Sabatté's graphic work revisits the fundamentals of drawing by revealing lines, densities, values and reserves in the dust he brushes onto paper, thus unraveling the masses of anonymous portraits awaiting their revelation.

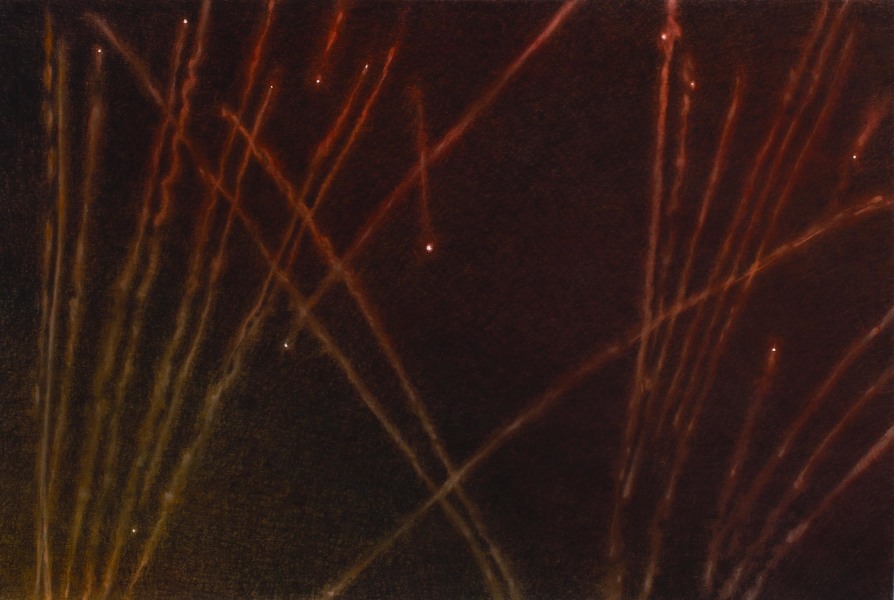

Beyond the significance of the topics he tackles, it is really the material’s agency that drives Nicolas Daubanes to act. He constantly updates the processes he employs, drawing on various states of steel to create an unexpected graphic repertoire. From this polymorphous material, the artist draws a set of forms and narratives, driven by an almost kinetic energy leading him from one gesture to the next. The use of magnetized iron filings—which he combines with sawed-off prison bars—leads him to take action. Armed with an iron bar and an angle grinder, the artist projects particles of incandescent steel onto glass. Sensitive to thus generated light, he draws photograms from its flashes, in which the insolation produced by the sparks outlines ballistic or stellar trajectories. By seizing upon steel industry slag and workers' tools, Nicolas Daubanes multiplies the meeting points between sculpture, photography, and drawing. He forges a language in which matter—in the gravity of its contained fall, its incandescent liquidity, or the immateriality of its light—becomes an inexhaustible graphic operator.

As the surgeon sculpts the new face chosen and drawn by the artist, ORLAN produces a series of self-portraits that challenge notions of identity and resemblance. The five faces presented in the exhibition serve as relics that extend the surgical act, revealing the full range of possibilities: every conceivable face that can be created from raw flesh, as supple and malleable as clay. These spontaneous and impulsive blood drawings are created urgently, before the wound closes. It is an infinitely tactile graphic gesture, testing the viscosity of the blood and its adherence to different surfaces under one's fingertips. On display for the first time at this exhibition, these drawings appear as jubilant artistic improvisations, anticipating the Self-Hybridizations series of the late 1990s. The expressiveness of these masks stems less from the fact that they are among the few works literally “by the hand” of the artist than from the nature of the vis-à-vis they establish: veiled presences, prisoners of their materiality, usually kept secret and which, herein, fundamentally emerges. The intimacy that unfolds in these faces, born of gestures in the form of countless caresses, pierces our own skin. They combine skin and flesh on the same surface, just as they summon the other within oneself.

This gesture is also that of Gloria Friedmann, who reconnects with a freedom that academicism might have caused us to forget. This gesture, which was already made possible by damp clay found in caves, seems to be the common denominator for all unarmed sketchers when they have to tackle the surface with their bare hands. Fragile, without artifice or safety net, like a skater abandoning themselves to the pleasure of freeing themselves from all gravity, the finger glides over the damp surface to trace the telltale tracks of these convolutions. By drawing these animal figures, the artist brings new species to life that are strangely familiar. Contrary to Jean Clottes' shamanic perception of cave art—which consists of killing the animal in the image to facilitate hunting—the bestiary produced by Gloria Friedmann tends to retain its “Animalia” with an immemorial gesture, conjuring up the possibility of their disappearance.

In the Artifice series, Rémy Jacquier's tracks are the result of manually removing the calcined powder deposited by charcoal. By lightly grazing the surface, the artist brings back the shades it had covered. The gesture intensifies when a drypoint scratches the paper to restore its immaculate white and obtain the luminous punctuation marks that pierce the darkness of the sky. Geographical references in the titles divert the trajectory that seemed to be all mapped out. Exhibited for the first time, the three 1996 drawings suggest that the cigarette is an allotropic form of charcoal. It offers shades of gray and a workability that allows the artist to bring out feminine silhouettes taken from sculpture history: forms consumed by their dissemination throughout the history of representations.

Tania Mouraud's works, on the other hand, seem to keep drawing at arm's length, leading it towards a nearly intangible existence, pushing it back to the point of literally making it sink into the paper. Through a process of embossing, the artist combines monochrome—which might suggest that there is nothing to see—with set phrases—which consist of saying practically nothing. If these writings defy any attempt at interpretation, it is because the artist, although accustomed to making us feel estranged from our own language, has chosen Yiddish. In these deliberately ornamental forms, Tania Mouraud orchestrates an apparent loss of meaning. They are singularly reminiscent of the meanings hidden in certain ornaments, like encrypted messages discreetly addressed to those capable of understanding them.

Dylan Caruso, curator